A recent brief article in the Revue du Vin de France about organic and biodynamic wines made us think that it is probably a good idea to explain the differences between organic, biodynamic and natural wines in this newsletter and to talk a little about the backing and authority for each, the certifications for each type, and also some of the organisations that winemakers can belong to and the charter practices that they must adopt.

This piece was also timely because in the last couple of months we have seen the Return to Terroir event in Melbourne (mentioned elsewhere in this newsletter) which saw over 70 biodynamic winemakers from around the world who adhere to strict biodynamic practices both in the vineyard and in their cellars come together to show their wines to both the trade and to the public at a very well-attended event over two days.

Another event which was held in Angers at the beginning of February was by the certifying authority Demeter which has now moved from certifying vineyards as bio-dynamic to certifying the winemaking practices as well. They held an event for winemakers who have Demeter certification to display their wines to the public to give a higher profile to the certification.

And of course there are legislative rules being enacted in Europe and associations being formed to ensure that winemakers who use the words such as organic, biodynamic or natural are conforming to the commonly accepted requirements for such wines. Let’s now look at each of these in turn to determine what the differences between them actually are.

Organic wine

The term organic viticulture refers to the organic treatment of the vines in the vineyard. No chemicals or poisons can be sprayed on the vines or the ground to combat disease or attacks from predators. No artificial fertilisers can be spread on the vineyard to promote or enhance the growth of the grapes.

There are many organisations throughout the world that certify that growers are organic. One of the most active is Demeter.

Not all vignerons who grow their grapes organically can claim to produce organic wine, however. Some use terms such as “wine made from organic grapes” when they are organic in the vineyard but not organic in the winery. Such winemakers add non-organic products such as yeast or fish meal or bentonite which may not be organic.

And of course this raises the question of whether there are any advantages to using organic grapes.

A recent study[1] addressed the key issues of nutrient value and levels of pesticide residues in organic and non-organic food and found that organic food has a 19% higher level of beneficial polyphenols and a much lower level of pesticide residues and cadmium residues than conventional products. This was a massive study conducted by a large number of researchers who analysed some 343 peer-review published articles to come up with their conclusions.

Recent updated legislation introduced into the European Parliament[2] now regulates the term organic wine and is quite specific about what can and cannot be included in the wine. The first absolute requirement is that no synthetic pesticides or herbicides can be used on the vines or under them. In addition, artificial fertilizers cannot be used in the vineyard.

Section 7 of this Regulation is very specific about certain winemaking practices as well, ruling out the following:

- Concentration by cooling (Article 29d 2(a))

- Dealcoholisation of wine (Article 29d 2(d))

- Elimination of sulphur dioxide by physical process (Article 29d 2(b))

- Electrodialyses treatment for tartaric stabilisation (Article 29d 2(c))

- The use of cation exchangers for tartaric stabilisation (Article 29d 2(e))

In addition, the Regulation fixes a maximum limit for added sulphites with that limit being significantly below that for non-organic wines.

Article 29c reinforces the fact that products used in organic wine production shall be produced from organic raw material. Therefore, while it does not enforce indigenous yeasts for fermentation it does require that commercial yeast added to the wine must be made from organic products, which often they are not.

Other practices have been allowed in the interim, however the commission has indicated that they are likely to be banned this year. These are:

- Heat treatments of the wine;

- Use of ion exchange resin;

- Reverse osmosis.

Winemakers conforming to the rules of the EU set out in this Regulation and the other Regulations it enforces are entitled to use the “Organic logo of the EU” on their products as shown below.

Biodynamic wines

A more rigorous, and ultimately more successful and rewarding, approach to management of the vineyard is the application of the biodynamic processes espoused in the 1920s by polymath Rudolph Steiner – the same person who established new methods for teaching children through the Steiner schools.

Some in the industry are passionate believers in biodynamics others deride it as lacking a scientific basis and being more of a belief system than an approach to agriculture. They point to burying manure in cow horns to create a starter for biodynamic sprays and tending the vines at midnight during certain phases of the moon as being examples of the edginess of this approach.

All we can do is look at the results. When we wander through the d’Meure vineyard in southern Tasmania we see a vineyard that is alive! There are worms and spiders and ladybirds and insects and crickets all keeping an eye on each other. We see wasps captured in spiders’ nests before they can damage the grapes. Above all we see incredibly healthy grapes.

The same, almost magical experience can be had by clambering over the rocky, wind-swept vineyards of Anne-Marie and Pierre Lavaysse in the Languedoc in France, where there is an incredible diversity of both flora and fauna – and healthy, flavoursome grapes. On the other side of France, Thierry Michon has turned marginal land near the Atlantic shores into a large (37 hectare) productive vineyard where delicious wines are produced under his Domaine Saint Nicolas label.

We also smile inwardly when people denounce biodynamics as mumbo-jumbo because it follows the phases of the moon and they say that the moon cannot have any effect on vines – but the same people are quite happy to accept that the moon exerts sufficient gravitational pull on the Earth to allow electricity to be generated from the massive tidal flows caused by the moon!

There is also a large body of scientific literature that supports each of the cornerstones of biodynamics which we will incorporate in a future blog. Ultimately, however, one of the main benefits promoted by biodynamic viticulture is healthy, “alive” soils which promote vibrant microbial life and healthy fungi which are vital for transmitting nutrients into the vines.

There are a number of organisations which certify biodynamic producers with the most active being Demeter and Biodyvin. The Renaissance des Appellations organisation which has many adherents throughout the world also has a strict set of guidelines regarding both biodynamic viticulture and natural fermentation.

Natural wine

Almost every article about natural wines that we read has somewhere within the text a statement such as “there is no agreement about what constitutes a natural wine”.

This is somewhat strange since we believe that there is quite good agreement throughout the various bodies such as France’s Vins Naturels and S.A.I.N.S, the international Raw Fair association and many others who run the very popular salons throughout the world such as the Dive Bouteille and Renaissance des Appellations (which has over 200 members in 13 countries), the certifying bodies for organic and biodynamic agriculture such as Ecocert, Qualité France, Demeter, biodivin, Nature et Progrès and many more.

Wines that are classified as natural have even more restrictions than biodynamic wines. They must be either organic or biodynamic in the vineyard and then must have no additions in the winemaking process except for a small amount of sulphur – although an increasing number of our winemakers use no sulphur at all. Of course, there may be some sulphites naturally generated during the fermentation process.

The next requirement for a wine to be classed as natural is that the wine is fermented only with the natural yeasts that are found on the grapes and in the winery. These long, slow fermentations are generally quite gentle and produce fewer harsh polyphenols and a more complex mix of flavonoids and anthocyanins due to the greater number of natural yeast varieties found in the vineyards.

We have written before about how the term natural wine has been widely used for hundreds of years[3], however Governments have been slow to legislate to define what a natural wine is, even though consumers throughout the world who drink them are in no doubt.

It has been left, in the main, for professional associations to define the standards for natural wines and there is a remarkable similarity between their requirements. For example, in France L’Association des Vins Naturels has a very clear statement of philosophy in relation to natural wines. For a wine to be natural:

- Vineyard practices must be in accordance with organic or bio-dynamic practices;

- The harvesting must be manual;

- Only indigenous yeasts can be used for vinification;

- No use of brutal and traumatic physical techniques such as reverse osmosis, crossflow filtration, flash pasteurisation or thermovinification, and

- No inputs added except for a little sulphur.

Under their charter the “no inputs added” requirement includes any inputs to the wine that are used for fining. Thus no bentonite, no fish bladders, no egg whites or any other additives can be used to strip out flavour from the wine.

These requirements are almost identical to those for the Renaissance des Appellations organisation headed by Nicolas Joly. The only area where they are silent is in the use of new wood, which we don’t like to see because it results in adding chemicals from the wood (lignins) into the wine. We prefer the use of old wooden barrels and foudres where the lasting taste of those chemicals has been removed from the wood or some sort of inert vessel.

We were therefore interested to read recently about efforts by a group in France that includes one of our suppliers Jacques Carroget called the “Syndicat de défense du vin nature”. They have been working with the French Ministry of Agriculture, the DGCCRF (Direction Générale de la

Concurrence, de la Consommation et de la Répression des Fraudes) which in English is the General Directorate for Competition, Consumer Affairs and Fraud Control and France’s powerful National Institute of Origin and Quality (INAO) that controls the rules for every wine appellation in that country to develop a branding system that will provide consumers with a branding system that will provide comfort that a wine has been produced in accordance with the rules associated with natural wine production.

They are working towards acceptance of the label “vin méthode nature” and an associated logo that can have one of two descriptors. These will be ‘with no added sulphites’ (for sulphite concentrations below 10 milligrams per litre) and the second ‘less than 30 milligrams per litre of added sulphites’ to define an upper limit to the level of sulphites used. If the 30 milligrams per litre is exceeded then the winemaker would be denied the use of the logo.

And in breaking news the magazine Terre de Vins on the 10 March 2020 has published an article entitled “La dénomination “Vin méthode nature” est née” which in English states “The name “Vin méthode nature” is born”. The article also mentions the agreement of the DGCCRF mentioned above that if a winemaker uses the logo without adhering to the charter then they are committing fraud. So, there is now Government backing in France

that protects natural wine!

It also means that there is protection for the Charter of the Syndicat de défense du vin nature which, in summary, requires the following:

- The grapes must be 100% organic and certified by either Nature & Progrès or the European Agriculture Biologique certification (which includes Ecocert);

- The grapes must be manually harvested;

- The wine must be fermented naturally;

- There must be no additions which means no fining or adding something like megapurple, for example;

- No “brutal” techniques such as those mentioned above;

- No sulphites added before or during fermentation;

- If sulphites are added before bottling the level must be below 30 milligrams per litre and a different logo used.

The article mentions that 50 winemakers have already joined the association and they expect 500 to join soon. Let’s hope that this idea spreads to other countries including Australia.

Importantly, the French Government’s Ministère de l’Économie de l’Industrie et de l’Emploi a few years ago issued a decree about claims to natural products and this decree addressed in part claims of wines being natural.

In a Note d’Information (number 2009-136) issued on the 18th August 2009 it set the rules for what constitutes a natural product.

Since the issue of this decree it has been illegal in France to use a term such as naturel, vin naturel or vin nature unless it conforms to the guidelines set out in the document. (Note that the decree was broader than just wine, but we will stay focussed on this topic!).

The document deals with processes that can change the nature of a product and hence changes it from the natural state. Examples of processes that are not allowed for products that claim to be natural include pasteurisation, ultrafiltration, genetic modification or reverse osmosis, among others.

So, if a product has undergone any of these transformations it is not permitted to have any words on the label that indicates that it is a natural product. And, of course, none of our winemakers use any of these processes because they alter the basic nature of the wine.

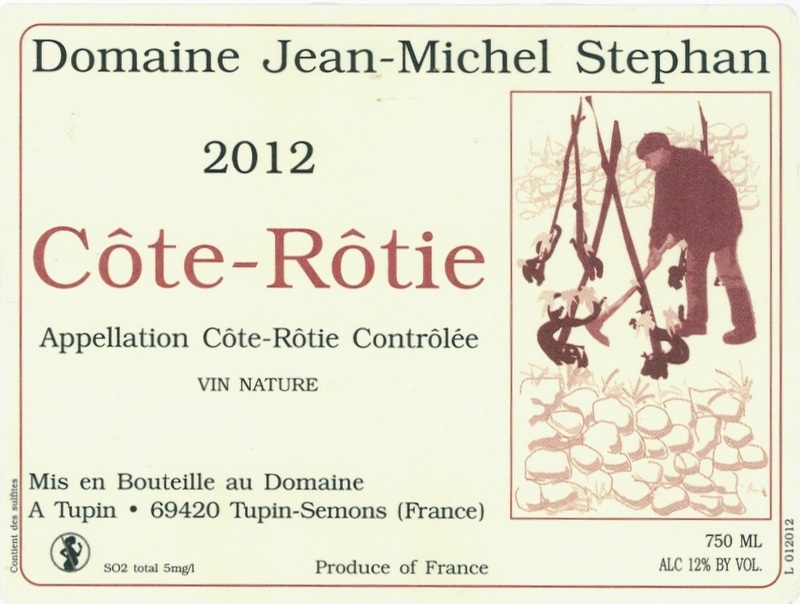

Now let’s have a look at a label from one of our suppliers, Jean-Michel Stephan from the northern Rhone in the Côte Rôtie.

You can see from this label that he quite clearly states that this wine is a Vin Nature. This means that the wine conforms to all of the restrictions laid out in this decree. Of course, Jean-Michel has for the past 17 years never even added sulphur to his wines let alone any of the other additives used widely in winemaking.

[1] Baranski, M. et al (2014) Higher antioxidant and lower cadmium concentrations and lower incidence of pesticide residues in organically grown crops: a systematic literature review and meta-analyses.British Journal of Nutrition. 112, 794 – 811.

[2] European Union Regulation No 2013/2012